Quentin Jammer drops a rare and raw truth today. The former Chargers cornerback says he played multiple NFL games in 2011 while drunk, a decision he ties to a painful divorce. He calls the admission part of his recovery, and says he has been sober for two years. This is personal. It is also a window into how the sport handles crisis behind the scenes.

What Jammer Revealed Today

Jammer did not hold back. He wrote that he was, in his words, “completely s‑t faced drunk in at least 8 games” during the 2011 season. He described carrying two bottles of tequila in his bag. He says he drank during games and again on the ride home. He pointed to a blown coverage on November 20, 2011, and says his state played a role.

He also suggested the Chargers knew he was struggling that year. That raises hard questions for a team that finished 8 and 8 and leaned on him as a veteran starter. Jammer was 32 then, a physical corner who tackled well and lived press coverage. He was also going through a divorce. Today he says the pain pushed him to drink, even on game days.

Jammer says he was intoxicated in at least eight games in 2011 and is now two years sober. He frames the admission as part of his recovery.

This is uncommon in pro sports. Players hide pain. They tape ankles, take shots, and keep moving. Admitting alcohol use during games, and detailing how it happened, is something else. It is honest. It is also alarming.

The Football Context

To understand the weight, you have to know the player. Jammer, born June 19, 1979, was a unanimous All‑American at Texas. The Chargers drafted him fifth overall in 2002. He played 11 seasons in San Diego and one in Denver in 2013. He finished with 21 picks, about 130 pass deflections, and roughly 733 tackles. He was steady, tough, and respected.

The 2011 Chargers needed that steadiness. They were talented, but uneven. Norv Turner’s team went 8 and 8 and missed the playoffs. Cornerback is not a spot you can hide. One wrong step can flip a game. If what Jammer describes is true, then coverage calls, leverage, and eye discipline were at risk. Every snap is read and react. Alcohol dulls all of that.

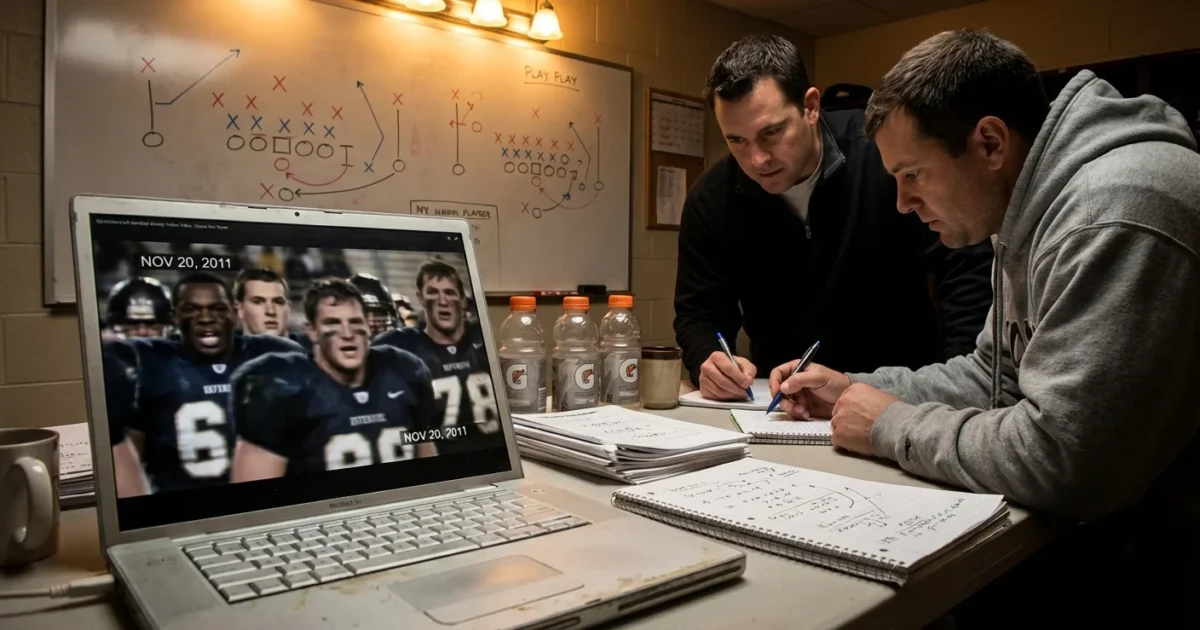

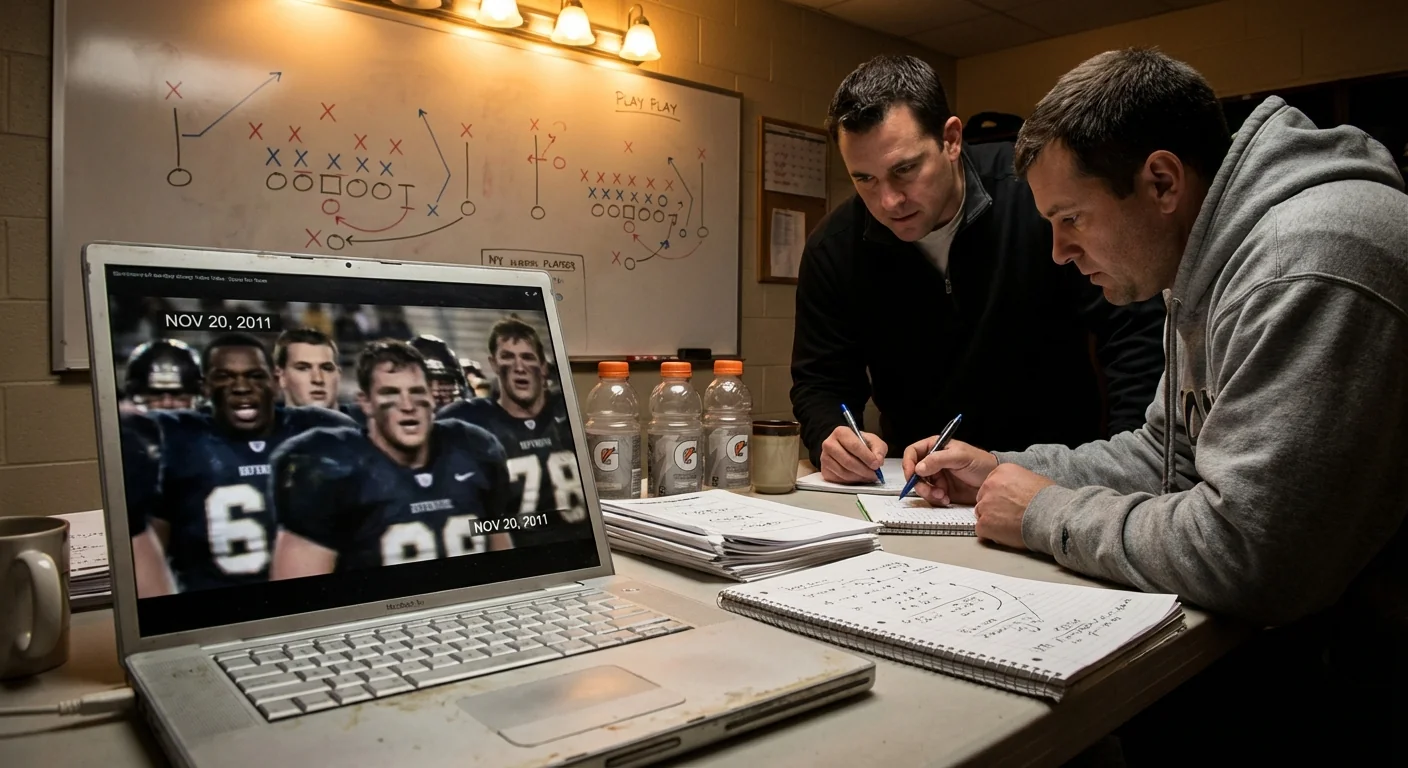

He specifically cited November 20, 2011. That was a messy day for the secondary, with miscommunications and stress points on the edges. A single blown coverage can be the difference. It lives on film. It lives in a room where coaches rewind the same play, over and over.

[IMAGE_2]

The Locker Room Reality

Players talk about protecting each other. They also talk about accountability. These can clash. Teammates see everything. Coaches see most things. Trainers hear the rest. When a veteran is hurting, the machine often keeps moving. Wins matter. So does the next install. The human part gets lost.

This story pulls that truth into the light. It asks what teams owe a player in crisis. It asks how far a player can fall before someone says stop. It also asks whether league policies are built for real life, or only for discipline.

Jammer’s legacy is complex, and it always was. He was a first round pick, a long‑time starter, and a tone setter. His admission adds another layer to how we view those years.

What This Means Now

Jammer says he is sober and moving forward. That is the best news. Recovery is work. Today is part of that work. It also leaves the sport with work to do.

Here are the questions that demand answers:

- What did the team know in 2011, and when did they know it

- What support was offered, and was it enough

- How should the league update reporting and care, not just punishment

- How do coaches balance winning with a duty to protect players

The NFL has improved mental health resources in recent years. More clubs have on‑site clinicians. More players speak up. Still, stories like this show gaps. Confidential care must be real. So must guardrails that keep a player who is not fit to play off the field, even on Sunday.

Jammer’s admission does not erase his career. It reframes a slice of it. It puts a human struggle beside the stat line. It asks fans to hold two truths. He was a high level pro. He was also a person in pain who made harmful choices. Both can be true.

Conclusion: Jammer’s honesty cuts through the noise. It is brave, and it is jarring. It forces football to look in the mirror, and it reminds us that even the toughest corners are not bulletproof. The next step is the hard one, better care and real accountability, so stories like this are told early, not years later.