BREAKING: Vanity Fair’s Trump Inner Circle Spread Ignites Legal and Civic Questions

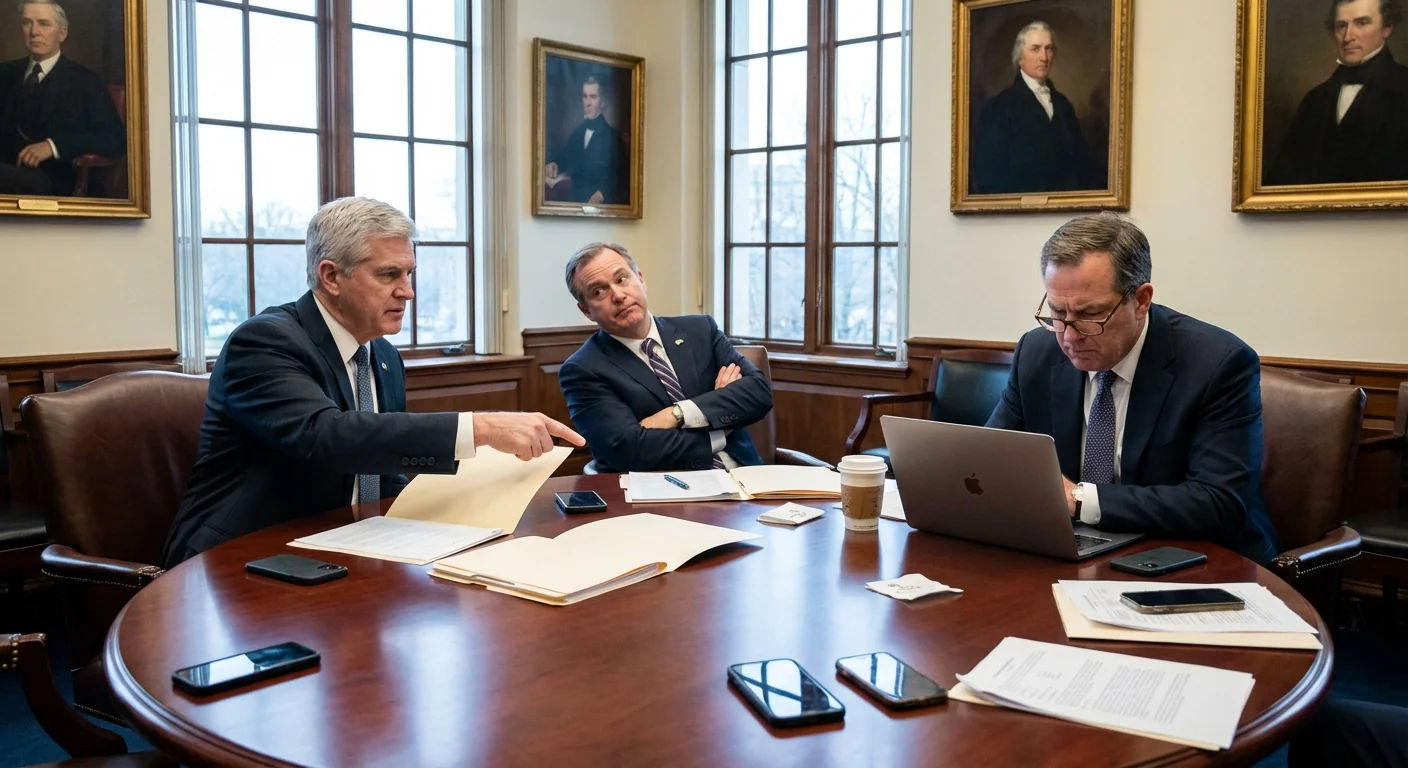

Vanity Fair has put former President Trump’s inner circle on glossy display, and the political fallout started immediately. The two-part, on-the-record feature, anchored by interviews with senior Trump adviser Susie Wiles, pairs intimate quotes with stark, stylized portraits that look like a cabinet-in-waiting. Within hours, Republicans accused the magazine of crossing lines. Senator Marco Rubio said the photos were deliberately manipulated. The clash is not only about taste. It is about law, policy, and how images can shape elections.

What Happened And Why It Matters

Vanity Fair released a multi-part profile that pulls the curtain on Trump’s tight team. The piece centers Wiles, a key player in Trump’s operation, and presents a supporting cast that could influence a future cabinet and senior staff. The photographs are striking. They set a mood. They also set off the fight.

We reviewed the package. The lighting and framing are stylized, which is common in magazine portraiture. That does not prove deceptive edits. It does underscore how visual choices can carry a message. The law usually gives wide room for that message. The First Amendment protects editorial judgment. That protection is strongest when public figures and matters of public concern are involved.

The Legal Lines Around Images And Words

Accusations of manipulation raise a core question. When do photo edits cross a legal line? There is no federal ban on image retouching in news magazines. There are norms, not hard rules. Most outlets avoid changes that alter the meaning of the scene. Cropping, color grading, and lighting adjustments are standard. Fabricating content or falsely labeling staged images as candid can create legal risk.

- Defamation and false light can apply if edits convey a false, harmful impression of a person.

- Right of publicity is less likely here, since this is news, not an ad.

- The FTC polices deceptive ads, but not typical editorial photography.

- Equal-time rules do not apply to magazines. They apply to broadcast, with key news exceptions.

Public figures face a higher bar. They must show actual malice to win a defamation case, meaning the publisher knew it was false or acted with reckless disregard.

If Rubio or others press this claim, the first step is often a demand for clarification or correction. Litigation is rare and hard to win in this space. Many states have anti-SLAPP laws that protect speech on public issues and can penalize weak lawsuits.

The GOP Response And The Media Ethics Debate

Rubio’s charge, that Vanity Fair deliberately manipulated images, pulls ethics onto center stage. Newsrooms typically disclose staged portraits. They also avoid changes that suggest new facts. Here, the magazine appears to have produced stylized portraits that signal power and tension. That is a choice. It is not proof of deceit.

The politics are obvious. Trump’s team wants control over its own brand, especially if these figures are seen as cabinet contenders. The magazine’s framing, cabinet-like and dramatic, can tilt public perception. That power makes campaigns nervous. It also makes voters curious.

Policy And The 2024 Stakes

This feature will echo into the campaign season. It shapes early views of a possible Trump cabinet and senior staff. It also tests the press’s media exemption in campaign finance law. Interviews and editorial profiles fall within protected press activity. They do not count as contributions to a campaign. Only coordinated, non-editorial services with clear value might raise FEC questions. Nothing in this package, as presented, meets that threshold.

What happens next will depend on transparency. Clear captions, consistent labeling, and open communications reduce confusion. If the campaign reuses the images, licensing and consent matter. If outside groups cut the photos into ads, that pulls the FEC squarely into the picture.

Look for credits, captions, and labels. Portrait, illustration, composite, or documentary. Those words tell you how to read the image.

Citizen Rights And What To Watch

Voters have a right to receive information and to critique how it is presented. Press freedom is broad, and that benefits the public. But ethical lines still matter. Demand clarity. Ask campaigns and outlets to disclose how images were made. Expect labels when scenes are staged.

Watch for three things in the days ahead. First, any formal request for correction. Second, whether the campaign adopts or rejects the cabinet-in-waiting frame. Third, how other outlets cover Trump’s would-be cabinet, and whether they match tone or challenge it.

Conclusion

The Vanity Fair feature did more than showcase personalities. It tried to define a possible Trump cabinet and the circle around it, using words and powerful images. The GOP pushback, including Rubio’s allegation, forces a healthy check on how photography can drive public meaning. The law protects robust reporting and expressive visuals. The public’s job is to insist on clarity, then judge the substance. The campaign season just got a new frame, and the stakes are as civic as they are political.