Criminal defense is hitting a breaking point today. In two separate courtrooms, two high profile cases show the same strain. Money, ethics, and the right to a lawyer are colliding in real time. The stakes are not abstract. They reach into your Sixth Amendment rights and your ability to defend yourself when the government calls your property tainted.

Two flashpoints, one constitutional fight

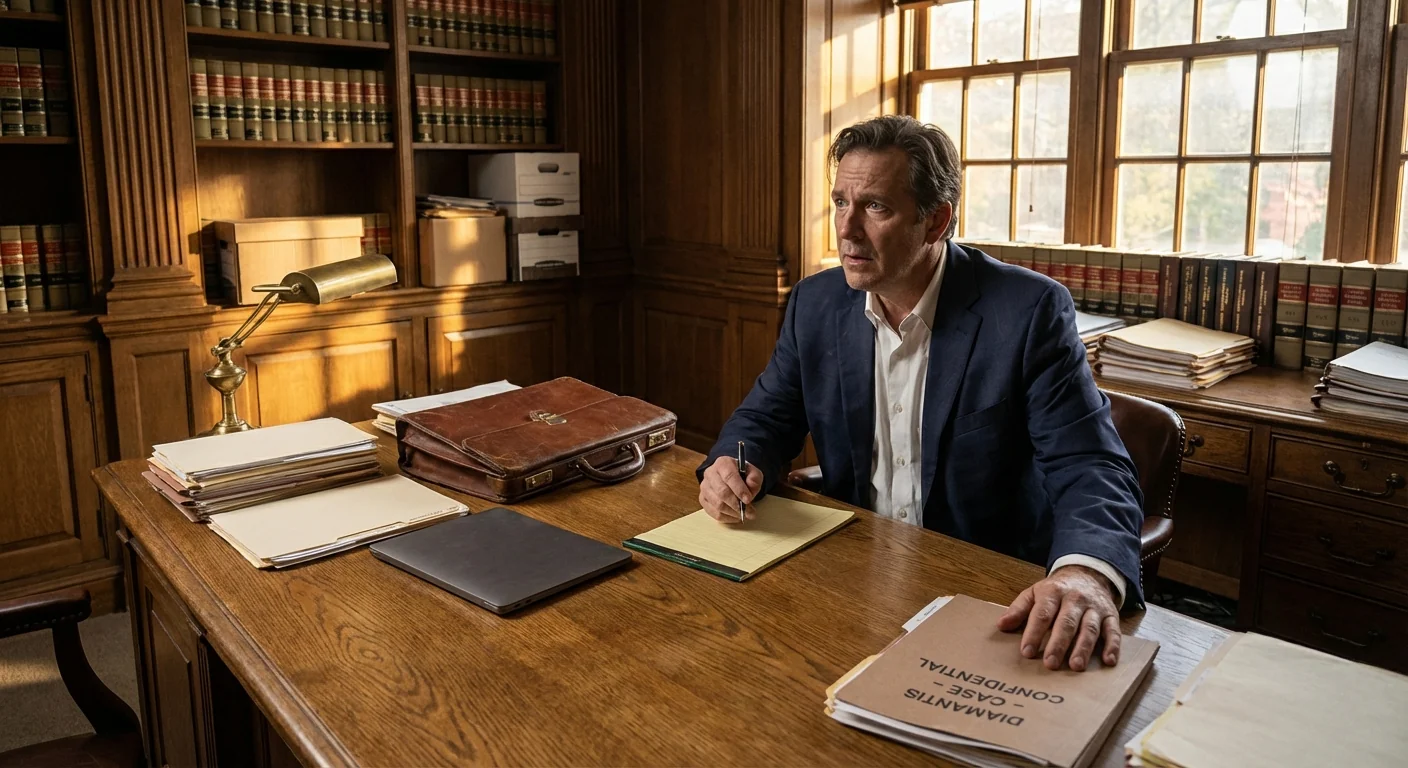

I have reviewed filings in two cases that tell a clear story. First, veteran defense lawyer Norman Pattis moved to withdraw from representing Konstantinos Kosta Diamantis, a former Connecticut official. He says unpaid fees from the last trial have created real hardship for his firm. Diamantis was convicted on 21 felony counts. A new trial is set for January 30, 2026. If the judge allows the withdrawal, Diamantis must hire new counsel or go into that trial alone.

Second, Tom Goldstein, the cofounder of SCOTUSblog, is facing 22 counts tied to alleged tax crimes. He wants court permission to sell his 3 million dollar D.C. home to pay for his defense. Prosecutors oppose the sale. They say the house is tainted, linked to alleged false statements. Goldstein has cycled through lawyers and now represents himself. The court must decide if he can use the house to finance counsel of his choice.

These are not side stories. They are the front line of the right to counsel when money runs short and assets are locked down.

The Sixth Amendment meets the billable hour

Your right to counsel is bedrock. It includes a right to hire a lawyer of your choice if you can pay, and a right to appointed counsel if you cannot. Courts also have a duty to keep cases moving, and to protect the integrity of proceedings. That is where the tension starts.

When a retained lawyer seeks to withdraw over unpaid fees, judges weigh fairness and timing. Courts ask if the withdrawal will delay trial, harm the client, or burden the system. Ethical rules often require withdrawal when nonpayment causes undue hardship or impairs the lawyer’s work. They also require lawyers to protect clients on the way out, including turning over the file and avoiding prejudice.

- What judges weigh in a withdrawal fight:

- How close the case is to trial

- Whether the client can get new counsel promptly

- The reason for nonpayment and hardship

- Risks to the orderly administration of justice

The right to counsel is personal and fundamental, but it does not guarantee a specific lawyer when fees collapse.

In the Diamantis matter, the court must balance Pattis’s hardship claim against the looming 2026 trial date. The judge can deny withdrawal, allow it with conditions, or continue the trial. Each option carries costs for the court and the defendant.

Can you use your own money to defend yourself

In Goldstein’s case, the core question is simple to ask and hard to answer. Can a defendant sell property to pay for a defense when the government says that property is tainted. Supreme Court precedent draws a firm line. The government can block assets that are traceable to crime. Those funds cannot be used to pay lawyers. At the same time, the Court has said the state cannot freeze clean assets before trial if the freeze blocks a defendant from hiring counsel.

So the fight turns on facts. Is the house linked to the charged conduct, or is it clean. Prosecutors say it is tainted through loan statements and bail terms. Goldstein says he needs the proceeds to hire counsel. The court can order a hearing to sort this out. The ruling will control whether he keeps representing himself or can bring in a new team.

Self representation is high risk. Even lawyers who know the system struggle as defendants. The rules and pressure are intense.

What these rulings will signal

Both courts are staring at the same policy fault line. Private defense is expensive. Complex cases require experts, data reviews, and time. When defendants cannot pay, private counsel withdraws. When the government marks assets for forfeiture, even wealthy defendants can be locked out of their own defense funds. Public defenders and CJA counsel cover many cases, but they are stretched thin nationwide.

Expect sharper litigation over fee disputes, asset freezes, and forfeiture. Expect more motions to withdraw. Expect more defendants to appear without counsel, at least for a time. And expect judges to demand clearer records, better disclosure, and earlier hearings on money questions.

If your assets are restrained, ask for a prompt hearing. Be ready to show which funds are clean and needed for counsel.